The outlook for UK small caps

How smaller companies are outperforming post-Brexit

The UK stock market has delivered some surprises over the past 12 months.

One year on into the pandemic, the principles for a promising investment have changed quite dramatically.

Big, defensive stocks, such as oil companies are out of favour, clashing both with the rise of ESG principles in stock selection, and the fact that they are large companies.

Something the pandemic has shown, is that those companies able to move quickly have been able to adapt to the changing circumstances; larger businesses, less so.

Now we are two months on from Brexit, what does the future hold now? Smaller businesses may not have the deep pockets of larger companies, but they are also able to experiment more, which can lead to success.

This guide, sets out to look at these issues and is worth an indicative 30 minutes' CPD.

Uncertainty grips advisers about economy

Advisers are sharply divided on the prospects for the UK economy in the coming years, according to the latest FTAdviser poll.

The poll, which was conducted via FTAdviser on Twitter earlier this month, showed that about 40 per cent of advisers were uncertain about the outlook for the domestic economy, while just over 30 per cent were optimistic, and 20 per cent are pessimistic.

The survey was conducted prior to prime minister Boris Johnson announcing his intended “roadmap” for the social and economic restrictions to end in the UK.

Such a roadmap, if the various time slots were achieved, might be expected to boost the prospects for the UK economy.

The poll was also conducted prior to the announcement that UK unemployment has risen to just above 5 per cent.

UK economy poll

The context behind that figure is that, while it is higher than has been in the recent past, 5.1 per cent is low by historical standards in the UK, and would have been regarded as “full employment” by the Bank of England until midway through the last decade, when the bank’s definition changed to 4.5 per cent.

The data needs also to be seen in the context of many employees being on furlough, and so not showing up in the data at this time.

Sterling has also risen sharply in value of late, indicating international buyers are relatively more optimistic on the UK outlook.

david.thorpe@ft.com

The outlook for UK small caps after Brexit

Despite all of the noise and the constant, intense, newsflow of the period since June 2016, when the Brexit vote happened, the market has behaved in quite a traditional way, according to Harry Nimmo, who manages about £2.5bn in UK smaller companies assets at Aberdeen Standard Investments.

He says that just as small caps began to underperform relative to larger companies in the years immediately prior to the global financial crisis, as the market was by then reaching its peak. But small caps then performed excellently, and beat larger companies in the years after the crisis.

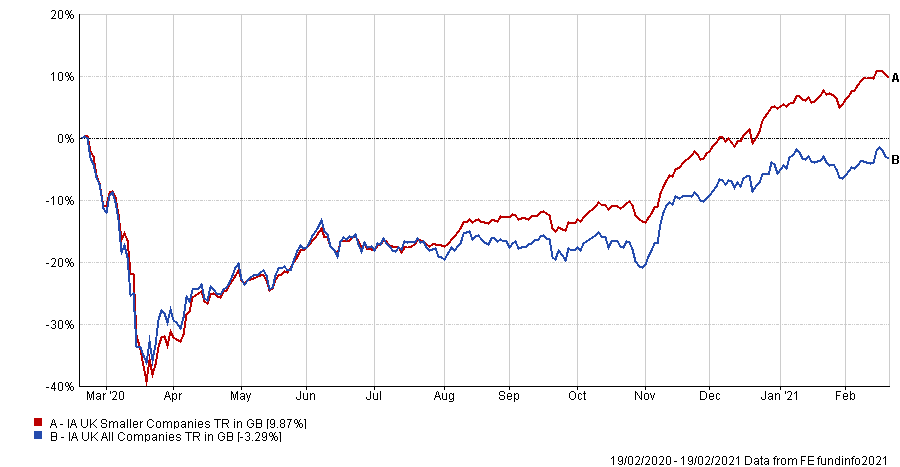

FE Analytics

FE Analytics

Nimmo says the small caps underperformed against large companies in 2018 and 2019, again as the market was reaching the peak of its cycle, before sharply underperforming from March 2020, when the onset of the pandemic brought the previous cycle to a close, while the discovery of the first Covid vaccine instigated the start of the new cycle, and the period where small caps perform best, in November 2020.

But while the impact of traditional market cycles on the performance of small cap shares has been strong, Nimmo believes that, in the UK at least, something more profound is happening.

He says the waves of technological and societal change that are happening in the UK and globally are rapidly making the FTSE 100 index of large companies “a wasteland” stuffed with companies “in sectors such as traditional banking, oil and mining” which Nimmo believes are structurally likely to lose out in a changing world, with the beneficiaries being the smaller companies that are unencumbered by legacy issues, such as digital banks and retailers.

Dan Green, who runs the UK Smaller Companies fund at Franklin Templeton, says 2020 was an “unusual” year in markets because, typically, when there is a cataclysmic market shock, “investors flee to safety, which should be bad for smaller companies, as those tend to be less liquid, and often have less established business models.

But, Green says, “the opposite happened. The theme of 2020 was that people were looking for the next trend, and small caps are where lots of the most technology can be found, the FTSE 100 has less than 2 per cent in tech, and some of that is in SAGE, which is not really a fast growing company.

“About 7 per cent of the small cap index is in tech, and on the AIM [Alternative Investment Market] that rises to about 15 per cent. The thing is, smaller companies can actually thrive in times of uncertainty, they are like speedboats, they can pivot quickly, while the larger companies are like tankers, they take ages to turn to new opportunities.”

The theme of 2020 was that people were looking for the next trend, and small caps are where lots of the most technology can be found

Victoria Stevens, UK small cap equity manager at Liontrust, says technological stars of the future are not the only way to make decent returns from companies further down the market cap scale.

Stevens favours companies where the management teams also own substantial stakes in the business, as, she says, this makes the companies “more resilient”, as they will have been run for the long-term.

She says many of those companies are found in less glamorous or exciting sectors, but continue to deliver strong returns in their area.

Stevens says that while the strong performance of smaller companies in the second half of last year means returns from the sector as a whole are lower, the companies that have thrived will be buying those that have not.

She says: “A feature of recent months has been the number of companies coming to market to raise capital, but not capital to survive, capital to expand and buy rivals.”

Nimmo says an irony of the small cap market is that “lower risk may be the way to higher returns, and that is the way we construct portfolios, with an element of the defensive in mind. We don’t want to own what I call ‘blue sky’ companies, those that are just an idea, and maybe haven’t made a profit yet.”

A feature of recent months has been the number of companies coming to market to raise capital, to expand and buy rivals.

Paul Marriage, who runs the Tellworth UK Smaller companies fund, says the domestic market has been “like the Millwall of investing since the Brexit vote, ‘no one likes us, we don’t care’, but the solution is not to buy oil companies, miners, or biotech, those are the casino end of small caps.

“The best small caps are probably a business on an industrial estate near you. But in recent years being underweight to the UK market has been rewarded.

“But since the Brexit deal the UK market has come in from the sidelines and become an investable market again, so people who were underweight stop being underweight, and that improves valuations, and then people move to small caps; in terms of the market cycle, that’s where we are right now. The retail investors are back in the UK market.”

Richard Penny, who runs the Crux UK Special Situations fund, which invests in all parts of the UK equity market says that while “history indicates where we are now is a time where small caps are cheap, you cannot let history be a total guide on its own. But there are some opportunities down there if you are careful, for example, the house builder shares rose quite a bit, but then fell back again, even though the fundamental factors impacting their businesses have not changed. The hospitality sector is tricky right now, and it looks as though it will be a long slow crawl back for the share prices of those companies, although they look cheap compared to history.”

Jochem Tielkemeijer, client portfolio manager at Natixis, says the outlook for smaller businesses relative to larger ones has been permanently altered by the impact of technology.

He says technological change makes it much easier to grow a business quickly, relative to history, and this reduces some of the natural advantages that larger companies have historically enjoyed.

Stevens says that while the valuations (in cash terms) being achieved by relatively new companies can appear dizzying, this is a function of how much easier it has become to grow a business quickly, in a world where more trade is done online.

Colin McLean, managing director and fund manager at SVM, says the events of the past year have permanently altered both the perception and the reality of smaller companies, and this means traditional arguments about the market cycle have become otiose.

He says: “UK small cap has undergone a transformation over the past 12 months, strongly outperforming large cap. Smaller companies are no longer seen as just a cyclical - and often illiquid and poorly governed - asset class; investors have woken-up to the potential for disruptive growth.

“In the aftermath of Woodford, more attention is paid now to share liquidity, but investors just need more care with portfolio construction, limiting size of holdings. There is a new dynamism in the sector; even small companies can dominate their niche and develop platforms with scalable growth.

UK small cap has undergone a transformation over the past 12 months, strongly outperforming large cap

“Growth can be rapid at an early stage although more companies are remaining private for longer and delaying a stock market listing. Some emerging businesses have taken market share from very big legacy businesses, such as many high street retail chains.

“Fevertree Drinks is an example of a disruptor. The UK has lagged many international markets in the aftermath of Brexit, but we believe that the resolution of Britain’s trading arrangements will bring a return of investors.”

Aiming High

When it was created in the early 1990s, the companies listing on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) stock market, which is owned by the London Stock Exchange, was festooned with extra benefits.

The intention of policy makers was to compensate investors for the extra risks accruing from investing in a nebulous stock exchange, filled with companies many of which were at the earliest stage of development.

As a result, any shares held by an individual in an AIM listed company are exempt from inheritance tax, while rules about financial disclosure are also more relaxed.

While most of the companies on AIM count as small cap, there is no requirement for firms to leave the alternative market when they reach a certain size.

Penny says the nature of the AIM market means that while there are opportunities for returns, “you have to go into it with your eyes wide open. There are a lot of frogs you have to kiss, before you meet that prince.

“The tax advantages mean there are a lot of retail investors in the market, and that helps with liquidity.”

Marriage says that in recent years the number of quality companies on AIM has risen, but is cautious on investing in the largest AIM companies, as it tends to be those which have risen most as a result of being bought by the retail investors keen on the tax planning angle. Those investors will get their return from paying less tax, and so are less concerned about buying more expensive stocks.

The tax advantages of AIM mean there are a lot of retail investors in the market, and that helps with liquidity

Green tends to prefer the AIM stocks that have large numbers of their shares owned by the company's founders. Such businesses are likely to stay on AIM as the founders then receive the tax advantages, but Green doesn’t think those companies, which are often quite large in size, are very well known.

He says despite the prominence of those companies, they don’t tend to trade at higher valuations than similar companies

He says: “The biggest AIM stocks performed well in 2020 as a result of the retail investors buying them, but I think the greater value may be in the smaller, more neglected parts of that market.”

Stevens says she is “agnostic” as to whether the companies she invests in are on AIM or the main market, indicating that the more lax rules of the former are not a particular disadvantage.

But her preference for owner managed businesses is validated to a greater extent on AIM, where many more such businesses exist because of the tax advantages for owners of remaining listed on that market.

Pexels/Artem Beliaiken

Pexels/Artem Beliaiken

Pexels/Burst

Pexels/Burst

Pexels/Anna Shvets

Pexels/Anna Shvets

House View: Trust me - I'm a chief executive

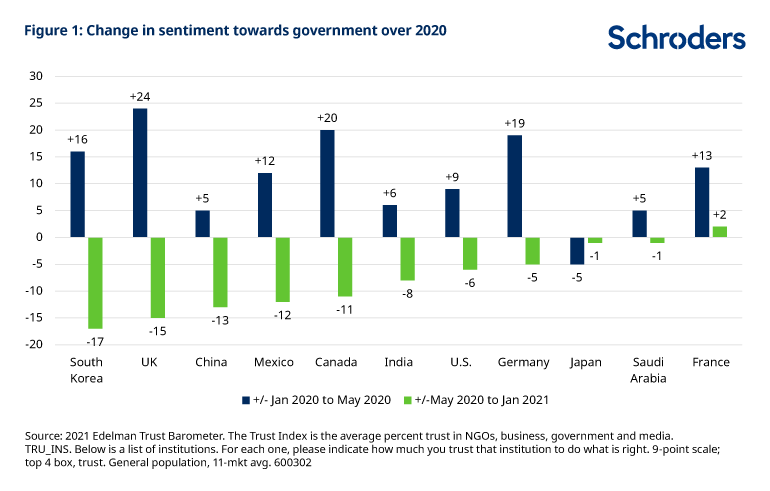

Public trust in government is waning, as the 2021 Edelman Barometer of Trust revealed recently.

Between January and May 2020, trust in government rose in almost all countries: people all over the world put faith in their leaders as the global pandemic took hold.

But, interestingly, this trust has subsequently eroded, in some cases to below pre-pandemic levels. The pandemic has been more severe and long-lasting than almost anyone expected, putting extreme pressure on health systems and causing unprecedented economic damage.

Distrust of government jeopardises recovery

Here in the UK, the government has been accused of flip-flopping and U-turns, undermining the ‘wartime mentality’ that prevailed in the spring of 2020.

In the US, it seems likely that Trump would have been re-elected if not for the pandemic. Lower levels of trust are threatening the recovery as many people are wary of accepting the vaccine amid swathes of misinformation online.

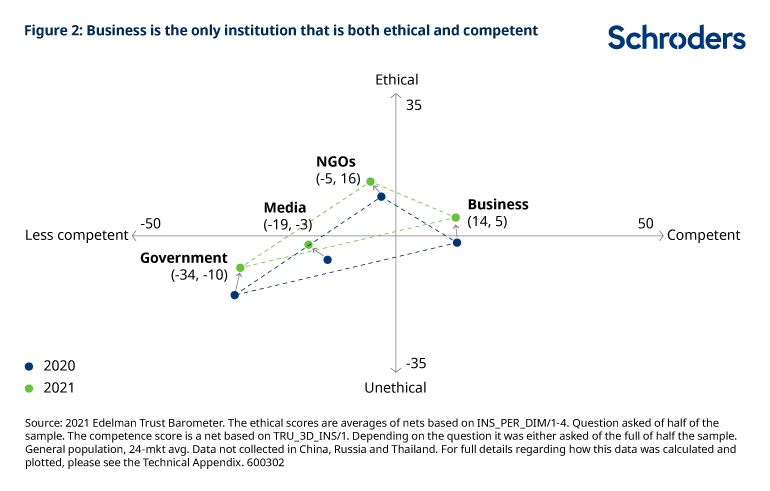

While trust in government is still up slightly on aggregate, Figure 2 shows that respondents see government as the least competent and the most unethical of all institutions.

Who can we turn to?

But it’s not all bad news.

There is one institution that is considered both ethical and competent: business.

Business is now the only institution to score over 60 on the Edelmann survey, the level which is considered the threshold for public trust.

It is gratifying to us that the big improvement has been in the perception of business ethics, reflecting well on the private sector’s response to the pandemic.

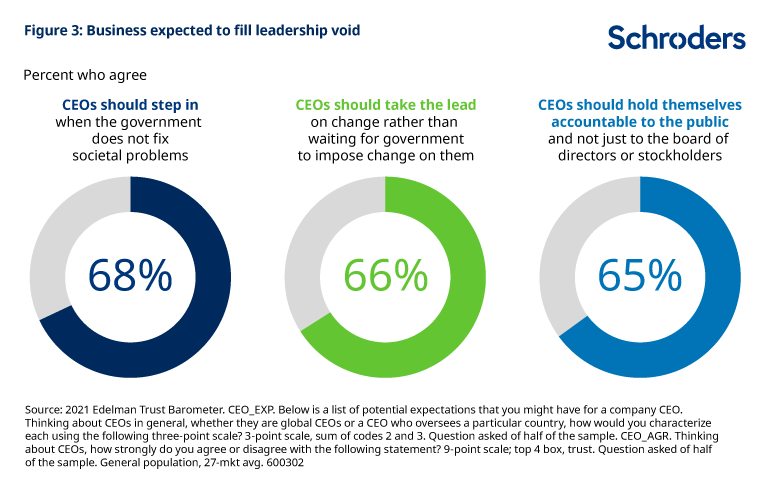

People are increasingly looking to corporates to step up and lead us not just out of the coronavirus crisis, but also to address wider societal problems.

A new social contract

This is consistent with our previous work noting greater public scrutiny on companies’ treatment of their stakeholders during the pandemic, especially with regard to employees.

We see this as the start of a new social contract between business and wider society.

We’ve seen growing evidence that investors expect companies to manage their impact on the wider environment and society, and lead on societal issues.

One relatively new phenomenon is that this trust is increasingly placed not just in the business community as a whole but on specific individuals within it.

This creates challenges for executives, who are now expected to publicly comment on contentious issues in order to maintain the loyalty of their customers, staff and shareholders.

Another question reveals that 86% of respondents expect CEOs to address societal problems, including the pandemic.

For example, now that “Black Lives Matter” has moved firmly into the mainstream, the vast majority of Americans surveyed by JUST Capital expected CEOs to respond to the BLM protests. It could be in the form of statement about ending police violence, promoting peaceful protest or, at very least, elevating diversity and inclusion in the workplace.

Business can and should rise to the challenge

The business community has a responsibility to be a force for good as this pandemic rages on. And we as investors have a responsibility to encourage and incentivise this behaviour. As stewards of client capital, we need to hold executives to account, encourage transparency, and support business leaders to act in the best long-term interests of society and the environment.

We have long believed that this behaviour will ultimately be in the best interests of shareholders, thanks to what we describe as ‘corporate karma’. 2020 was a powerful proof point, as we saw stocks and funds with higher ESG rankings outperform, especially during the sharp sell-off in March. We expect this to continue as customers, talent and capital flow to companies seen to be ‘doing the right thing’.

The public has put its faith in our hands; we – literally - can’t afford to let them down.

Katherine Davidson is portfolio manager, global and international equities